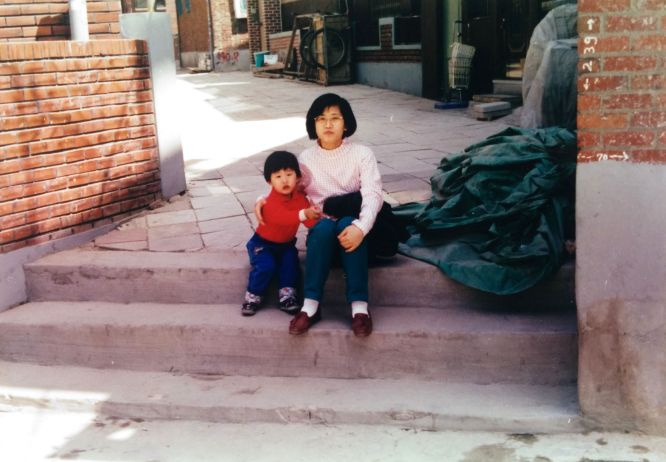

On my way home from my grandmother’s place, I noticed that the entire 4 blocks next to her place had been marked for clearing. My grandmother said an apartment complex is coming in. I stood there for awhile in front of those hollowed out stores and tried to remember it as it was. I had walked by those stores and houses every day last year on my way to the library — a small friend chicken place where an elderly couple were always bustling about, a pizza place that I never got to visit, an auto shop run by a handful of middle aged men, and our old 만화방 / comic book renting store on the hill. During the summer months, my mother would borrow an entire armful of Korean comic books from the 만화방 아저씨 and all three of us — my mother, sister, and I — would be splayed out on my aunt’s old bed binge reading them. My sister and I would be lying down in a neat assembly line next to my mother, waiting for her to finish the first book. But more often than not, we would become too impatient and start reading the second book, then when my mother finished she would hand me the book, and I would be reading everything out of order. The book traveled down the row from my mother to me then my sister, and by the end of the day, there would be a stack of an entire comic book series next to my sister, completed. The bookstore sat quietly, only reflecting back my own image under the street lamp. When I got closer, I could see that the place was now closed and completely gutted out, just like the rest of the area. All the building in the area were completely empty, and the outside of the buildings were slashed with blood red spray paint marking them for destruction: 철거 대상 / Target for Clearing. 이주 완료 / Move Completed. The words splashed so carelessly across their shop doors and signs that at first I couldn’t make out the words. In between the shops, there were old brick houses with 마당 gates that had been left open and piles of trash with accompanying rodents loitering outside their doorsteps. I had never known that there had been so many houses in that part of town. The entire thing made me feel hollow, like a chunk of myself had been taken from me. I didn’t realize that I had had a relationship with the people, the chatter, and the buildings of this part of town.

I wonder if this is what “development” and “progress” is supposed to feel like. People being ripped out of their homes and their absence left rolling around in the dark alleyways. And leaving the rest of us staring at dark windows and an eerie hollowness of the town, wondering when they are next. “시골같이 살 수 있는데가 없어,” my grandmother told me. I felt so helpless hearing that a large part of her life — the section of town that had sustained her relationships and daily routine away from my abusive grandfather — had all been cleared out. I wonder if companies think about stuff like that. The grandmothers who will now have to sit home alone instead of chatting with their friends at their favorite salon. The people who will forever look at the shiny new buildings and remember the ghosts of their childhood. Middle aged men who have lost yet another smoking-friendly gathering space to redevelopment. How many will miss their absent neighbors, how they will have to forge new connections with one another in an ever shrinking space, and how long we will remember the people of that neighborhood who once greeted us and welcomed us home.